Mental Health Resource and Practice Guide

Section 1: Introduction to Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

Welcome to the FASD and Mental Health Resource and Practice Guide for mental health professionals. This section will discuss:

What is Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder?

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) is a lifelong disability that impacts the brain and body of people who are prenatally exposed to alcohol. Individuals with FASD will possess unique strengths and areas of challenge1.

Watch the following video to hear more about what FASD is from Myles Himmelreich, a well-known motivational speaker who draws on his experience of living with FASD.

The Prevalence of FASD

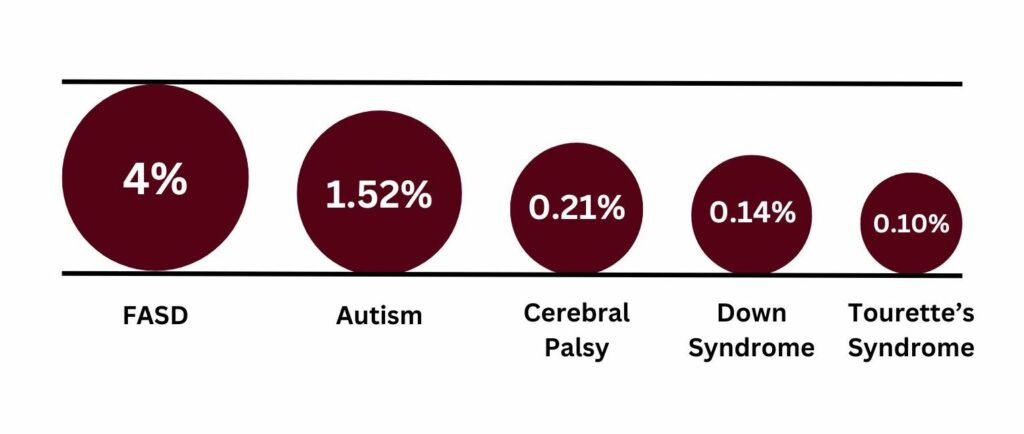

Prevalence estimates for FASD are challenging to obtain; however, the best current estimate for the prevalence of FASD in Canada is 4% of the general population (based on conservative estimates in two research studies, Popova, et al., 2018 & Thanh, et al., 2014)2.

When compared with other disabilities, FASD is one of the most common developmental disabilities in Canada, despite little public recognition or widespread understanding. More people in Canada have Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) than autism, cerebral palsy, and Down syndrome combined3:

FASD and Mental Health

It has been well documented since as early as the 1990’s that individuals with FASD experience mental health challenges across the lifespan, which can result in co-occurring diagnoses and other related difficulties. Despite this knowledge, there are few evidence-informed therapeutic responses and a considerable lack of research regarding approaches to supporting individuals with FASD4. As such, service providers and professionals may feel unprepared to appropriately and effectively work with people who have FASD.

Learn More

For additional information see CanFASD FASD Basic Information.

Misconceptions of FASD

Misconception 1: The physical presentation of FASD

Myth: All people with FASD “look different” or have a distinctive appearance.

Facts: Although previous diagnostic labels (e.g., Fetal Alcohol Syndrome) relied on the identification of facial characteristics associated with FASD, many individuals do not present with the characteristic facial features. Depending on the amount and timing of prenatal alcohol exposure, a minority of people exposed may develop these facial features and other growth differences. However, most people with FASD are not visibly “different”. Less than 10% of people with this diagnosis have distinguishable facial features associated with FASD5,6.

Misconception 2: FASD and IQ

Myth: All people with FASD will have a low IQ.

Facts: There is often an assumption that individuals with FASD will have a low IQ, and although this may be true for some people, it will not apply to others. IQ scores range in FASD populations, ranging from very high (above average) to very low (intellectual disability). In addition, knowing IQ alone is not sufficient to understand the challenges and strengths someone may present with.

Misconception 3: The lifespan of individuals with FASD

Myth: People with FASD have a shorter life span.

Facts: There is not sufficient evidence to suggest that individuals with FASD have a shortened lifespan, particularly examining individuals who have appropriate and tailored support. There is a myriad of factors that can impact the length and quality of an individual’s life and although FASD is a lifelong diagnosis, challenges can be circumvented with proper identification, education, and supports1.

Misconception 4: FASD, Race, and Culture

Myth: FASD is only an issue for particular communities or groups of people.

Facts: Despite popular misconceptions, FASD occurs in all segments of society. FASD is caused by prenatal alcohol exposure, and therefore any individual with exposure, regardless of social, ethnic, or cultural background, can have FASD. All populations where alcohol is used are at risk for FASD7. In addition, many Canadian women drink alcohol and approximately half of all pregnancies are not planned, which can lead to consumption prior to one finding out they are pregnant8.

FASD is of concern for many Indigenous communities, but this concern needs to be considered within the context of colonialism, intergenerational trauma, and historical and current social factors impacting Indigenous communities.

“The underlying factors contributing to FASD are related primarily to social background, including untreated or under-treated mental health issues, social isolation, histories of abuse… lower education levels, lower socioeconomic status, inadequate nutrition, a poor developmental environment, and reduced access to prenatal and postnatal care services. All of these factors can aggravate prenatal exposure to alcohol, drug use and smoking”7

It is also important to consider how the continued surveillance, stereotyping and stigmatization of Indigenous people can be contributing to this misconception9, as well as the over diagnosing of FASD within this population10. Examining our own biases and assumptions about FASD is imperative to stop perpetuating this judgement and misconception, which continues to marginalize Indigenous children, women, families, and communities9.

The following Toolkit was developed for Indigenous Families by the Ontario Federation of Indian Friendship Centers: FASD Toolkit for Aboriginal Families

Click on the dropdown options above to learn more about the misconceptions around FASD.

Stigma and FASD

I would feel freedom, inclusion, equality, a sense of belonging, a willingness to speak up and/or seek out help/support (without the cost of sacrifice as once required). We would build one another up, there would be less fighting, more accommodations, more diagnoses and families coming together.11

Stigma has important implications for individuals with FASD as well as their families through experiences of marginalization, negative stereotypes, lower self-esteem, and misperceptions about the person’s abilities9. Many people with FASD, as well as women who drink alcohol during pregnancy, feel judgement from society, including service providers and health professionals, which can prevent people from seeking needed services and support.9, 12

Children with FASD are often stereotyped as lazy, potentially violent, and can be labelled as having challenges with attention, learning, and social relationships11. Throughout the lifespan, as individuals become adults, this perception can result in more damaging stereotypes such as the belief that individuals with FASD are all involved with the criminal legal system and use substances.11 FASD as a disability is uniquely “criminalized” in the media as people with FASD are often portrayed as people who commit crimes, which perpetuates harmful and damaging misconceptions.13,14

For examples of common stereotypes and the prominence of stigma watch: “It’s Ignorant Stereotypes”: Stakeholder Recommendations to Improve Canadian Discussions About FASD

These stereotypes, compounded by a general lack of or misunderstanding of FASD, can create significant barriers to accessing appropriate and effective support. Such misconceptions can also damage an individual’s self-esteem and ability to see beyond the negative life trajectories often discussed as intrinsically linked with FASD10, 14, 15.

In addition, it is important to consider how intersecting oppressions can impact the stigma that someone experiences. Unfortunately, Indigenous people are particularly impacted by the stigma associated with FASD as the disability is often not contextualized as a social problem with connections to previous and continual colonization. Instead, racial stereotypes and misconceptions can continue to perpetuate stigma for Indigenous people with FASD7.

Shame and blame are commonly directed toward mothers and people who can get pregnant because of the discourse that they are causing harm to their child, a narrative that can greatly impact getting support or discussing alcohol consumption during pregnancy15. Parenting a child with any disability can be challenging, especially without a community and available resources. Parenting a child with FASD can be made even harder by the judgment and isolation that can occur, causing significant distress to parents, and by extension, to children16.

It is our responsibility as mental health service providers to ensure that we examine our own judgements and areas of bias, that could inadvertently impact our work and treatment of individuals with FASD. It is also essential that we continue to educate ourselves and advocate for the needs of our clients. To examine your biases please follow this link to Section 3.

An important consideration regarding stigma is avoiding stigmatizing language when describing individuals with FASD. The following language guide was developed by CanFASD and outlines some common expressions and ways to communicate that can help to destigmatize FASD: Common Messages Guide 2025.

Final Thoughts

As you move through the various sections of this resource guide keep in mind that people with FASD, or any disability, are more than just their diagnoses. Understanding what FASD is without letting it define who people are can be challenging, but it is our work.

Download Handout

For a summary of information, download the Mental Health Resource and Practice Guide Section 1 Summary.

References

1Harding, K. D., Wrath, A. J., Flannigan, K., Unsworth, K., McFarlane, A., & Pei, J. (2022). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: The importance of adopting a standard definition in Canada. Journal Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. DOI:10.22374/jfasrp.v4iSP1.10

2Flannigan, K., Unsworth, K., Harding, K. (2018). The Prevalence of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Vancouver (BC): CanFASD.

3National FASD strategy. CanFASD. (2023, February 21). https://canfasd.ca/national-fasd-strategy/

4Flannigan, K., Pei, J., McLachlan, K., Mela, M. (2022). Broad Approaches to Psychotherapy for Individuals with FASD. Vancouver (BC): CanFASD.

5CanFASD. (2019). FASD Basic Information. CanFASD. https://canfasd.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/FASD-Basic-Information.pdf

6Andrew, G. (2010). Diagnosis of FASD: An Overview. In Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: Management and Policy perspective of FASD (pp. 127-148). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527632510.ch7

7Wemigwans, J. (2008). FASD Tool Kit for Aboriginal Families. Ontario Federation of Indian Friendship Centres.

8Public Health Agency of Canada. (2016). The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2015: Alcohol consumption in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/canada/health-canada/migration/healthy-canadians/publications/department-ministere/state-public-health-alcohol-2015-etat-sante-publique-alcool/alt/state-phac-alcohol-2015-etat-aspc-alcool-eng.pdf

9Flannigan, K., Unsworth, K., Harding, K. (2018). FASD Prevalence in Special Populations. Vancouver (BC): CanFASD.

10Bell, E., Andrew, G., Di Pietro, N., Chudley, A. E., N. Reynolds, J., & Racine, E. (2016). It’s a shame! Stigma against fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Examining the ethical implications for public health practices and policies. Public Health Ethics, 9(1), 65-77. https://doi.org/10.1093/phe/phv012

11Morrison, K., Harding, K., Wolfson, L. (2019). Individuals with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and Experiences of Stigma. Vancouver (BC): CanFASD.

12Aspler, J., Zizzo, N., Bell, E., Di Pietro, N., & Racine, E. (2019). Stigmatisation, exaggeration, and contradiction: An analysis of scientific and clinical content in Canadian print media discourse about fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Canadian Journal of Bioethics, 2(2), 23-35. https://doi.org/10.7202/1058140ar

13Aspler, J., Zizzo, N., Di Pietro, N., & Racine, E. (2018). Stereotyping and Stigmatising Disability: A Content Analysis of Canadian Print News Media About Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 7(3), 89–121. https://doi.org/10.15353/cjds.v7i3.452

14Flannigan, K., Pei, J., McLachlan, K., Harding, K., Mela, M., Cook, J., … & McFarlane, A. (2022). Responding to the unique complexities of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 6712. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.778471

15Flannigan, K., Harding, K., Pei, J., McLachlan, K., Mela, M., Cook, J., McFarlane, A. (2020). The Unique Complexities of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Vancouver (BC): CanFASD.

16Green, R, C., Cook, L, J., Racine, E., Bell, E. (n.d.). Stigma, Discrimination and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Vancouver (BC): CanFASD.