Preventing alcohol use during pregnancy can positively impact parents, families, children, and communities. Because of the multi-generational nature of alcohol use, one change in service provision can multiply that impact many times over.

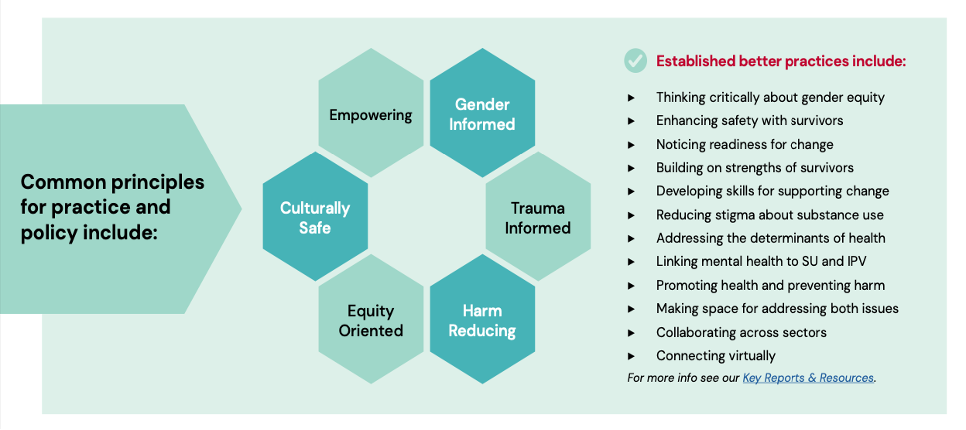

To prevent the use of alcohol while pregnant, health and social service providers can work to support people with a range of issues, including challenges with mental health, that may be impacting their alcohol and substance use. This is particularly true of providers who routinely work with women of childbearing age and use a range of approaches to support women and children’s health, such as women-centred care, social determinants of health, harm reduction, Indigenous wellness, trauma-informed, and strengths-based practice1.

This section will discuss:

Alcohol Use and Pregnancy

Globally, it is estimated that 10% of women consume alcohol in pregnancy2. Alcohol use in pregnancy can lead to miscarriage, stillbirth, premature birth, or result in FASD3. While many women stop or reduce their alcohol use at pregnancy recognition, some may face additional challenges when trying to reduce or stop their alcohol use due to the normalization of alcohol use, lack of pregnancy recognition, poverty, histories of trauma and violence, physical and mental health concerns, addiction, and child welfare involvement4. In addition, stigma can make it difficult for women to seek support5.

No alcohol is safest during pregnancy. However, for some, addressing alcohol use will also require attending to intersecting social and structural considerations. Throughout Canada, there are many approaches, programs, and supports available that provide assistance with reducing prenatal alcohol use and addressing health and social supports.

COVID-19, Mental Health and Substance Use

COVID-19 has had an immeasurable impact on people’s mental health and wellbeing. An interconnected and escalating concern during COVID-19 has been intimate partner violence, mental health, and substance use. During 2020, 1 in 10 women were concerned about their safety6. Women – particularly those with children – reported significantly worse mental health7, which may have led to an increase in substance and alcohol use. When providing services, it is important to consider the intersecting experiences that may contribute to people’s use of alcohol and other substances.

There are several common principles and practices to build upon to better link our responses:

Learn More

- For more information, please click here for an infographic: What we know about alcohol and pregnancy

- For more information and additional resources, please click here: Linking Practices on Intimate Partner Violence and Substance Use

FASD Prevention

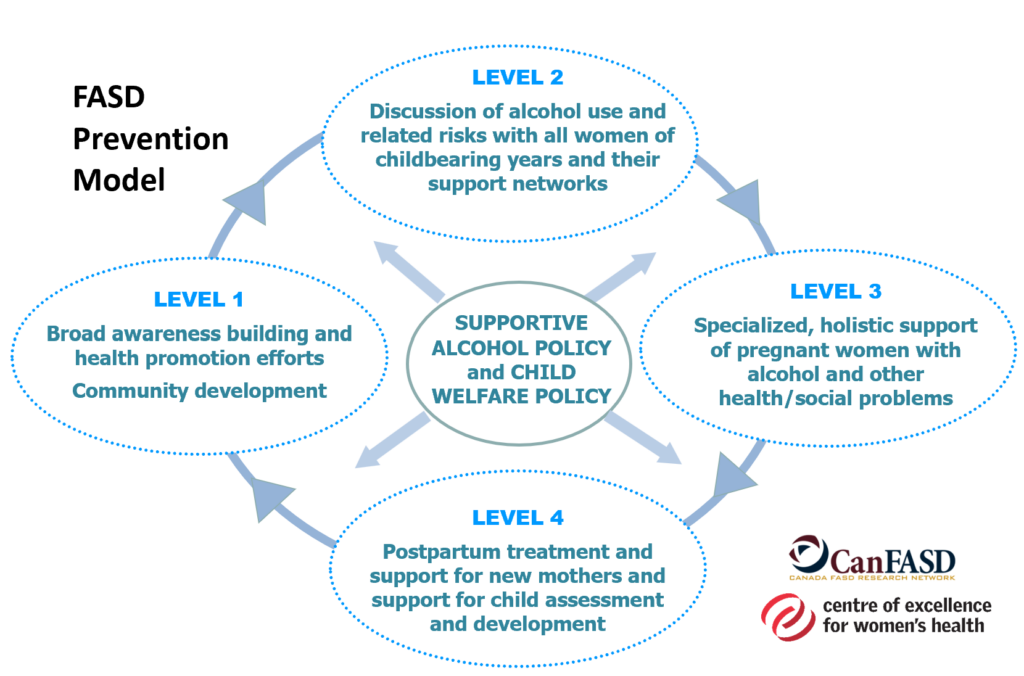

FASD prevention is incredibly complex and should use a holistic approach that addresses the numerous risk factors for drinking that are intertwined with the social determinants of health. In Canada, FASD prevention specialists have developed a supportive alcohol policy approach for individuals in a treatment setting based on the following four levels8:

Strategies to Enact the Four Levels of FASD Prevention

Click on the boxes below to expand the content and learn more about the four levels of FASD prevention.

FOR: All members of society

STRATEGY: Promote general public awareness at the community level, using campaigns and other broad strategies, of the negative effects of at-risk drinking. Public policy initiatives and promotion of girls’ and women’s health are key to this level of prevention.

FOR: All women of childbearing age, and their support networks. This level includes women who are not pregnant and do not appear to be at-risk for alcohol use.

STRATEGY: Use the opportunity for safe discussions about reproductive health, contraception, pregnancy, alcohol use, and related issues, with their support networks and healthcare providers.

FOR: Pregnant women who struggle with alcohol use and/or other social or health problems.

STRATEGY: Recovery and support services that are specialized, culturally safe, and accessible for women with alcohol problems, histories of violence and trauma, and related health concerns. These trauma-informed, harm-reduction-oriented recovery services are needed not only for pregnant women, but also before pregnancy and throughout the childbearing years.

FOR: New mothers who have problems with alcohol use.

STRATEGY: Postpartum support for new mothers in maintaining healthy changes made during pregnancy. A special focus on supporting mothers who were not able to make significant changes in their substance use during pregnancy is vital to assist them to continue to improve their health and social support, as well as the health of their children.

Learn More

- For more information please visit: Prevention of FASD: A multi-level model

Fundamental Components of FASD Prevention

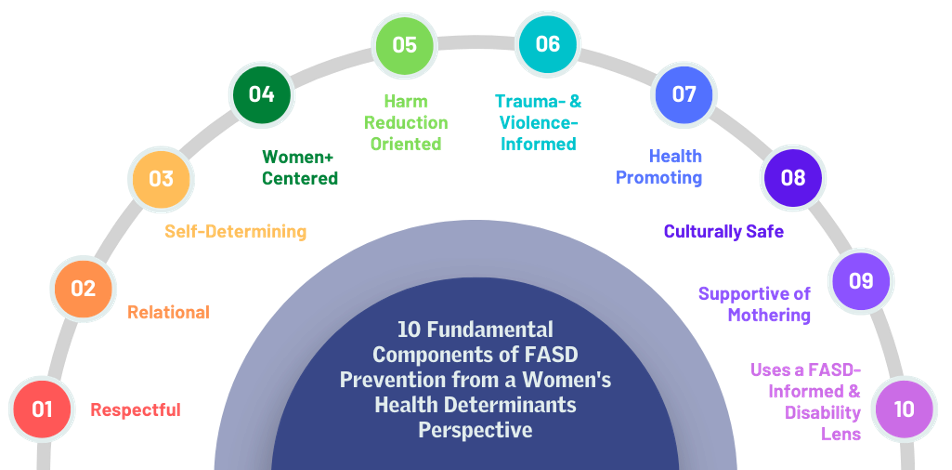

Ten fundamental components have emerged as key approaches to FASD prevention from a women’s health determinants perspective. These components originally emerged from a working session of the Network Action Team on FASD prevention (pNAT) held in Victoria, B.C., Canada in March 2009 and were updated in 2022 to weave in updated wisdom and resources.

For a description of each component and resources demonstrating how they can be enacted, click here: 10 fundamental components of FASD prevention from a women’s health determinants perspective

Promising Practices for FASD Prevention

Engaging in Brief Intervention and Support

Discussing alcohol use with all girls, women, gender diverse individuals, and their support networks is important. Brief interventions can be used to educate, provide support, and empower individuals to make changes to their health and prevent prenatal alcohol exposure1. However, fear of child apprehension, shame, guilt, and lack of social support can be a significant barrier to discussing or seeking help about substance use and related concerns9,10.

Recognizing the interconnections with stigma, violence, trauma, mental health, and substance use are important when engaging in brief interventions. Brief interventions are very effective where relationships and trust have been built to ‘meet women where they are at.’ This approach creates a space to respond using a social determinants of health perspective, which recognizes the many reasons for which individuals may use substances This relational approach can also facilitate safe and trustworthy discussions and can prompt engagement in support and/or treatment, as appropriate1.

It can also be important to remember:

- The pervasive role of alcohol in our society, which can make it difficult to avoid alcohol use in pregnancy11.

- There remains a lot of misinformation about the risk of multiple substances, including alcohol, during pregnancy. Service providers must be well-informed about the risks of alcohol and other substance use.

- Remember: no alcohol use during pregnancy is safest. For the latest guidance on Alcohol and Health visit: Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health

Brief interventions can be done formally or informally, and depending on your setting and/or role, you may choose to also use a formal screening tool. Most successful brief alcohol interventions include:

- Awareness raising through discussion of risks and assessment of readiness for change;

- Advice including provision of written or web materials and discussion of strategies for reducing or eliminating problematic alcohol use; and,

- Assistance in the form of eliciting ideas about change strategies, supporting/enhancing readiness, goal setting to reduce or eliminate alcohol use, positive reinforcement, and/or referrals to supportive services1.

Screening for Alcohol Use in Pregnancy

Depending on the role and setting that you work in, screening can help providers effectively inquire about prenatal alcohol use. While screening is often seen as the first step before brief intervention, it is important to create a trusting and non-judgmental relationship prior to engaging in screening.

Screening can:

- Allow for appropriate interventions to be applied at the earliest possible point;

- Give the client permission to talk about drinking;

- Help to identify and or clarify co-occurring issues;

- Minimize surprises in the treatment process; and

- Lead to more effective treatment or referral to related concerns12.

It is important to link brief intervention and support to screening and to referral for further support or treatment.

Screening should be conducted universally, regardless of someone’s gender, race, ethnicity, or economic status. Beyond identifying clients who are at risk of heavy alcohol use or misuse, screening can help promote awareness of alcohol use and can normalize conversations about substance use. Screening for alcohol use in male clients is also important, as research shows that partners’ drinking patterns can impact the drinking behaviour of expectant mothers13.

Some social service providers may not feel as though screening fits within their model of care because of their practice approach or that the tools are not validated or appropriate for the sub-population of women and girls in which they work. When screening does not fit into your model of care or healthcare setting, brief intervention and support as well as referral to appropriate services, can ensure that women, girls, gender diverse individuals, and their support networks are supported to reduce their substance use1.

For those who are in a position to use a formal screening tool, the AUDIT-C is a commonly used tool to identify a) frequency of alcohol use, b) quantity of alcohol use, and c) frequency of heavy (binge) drinking14. It was developed by the World Health Organization. The full AUDIT may be helpful as a follow up to support the identification of an alcohol use disorder.

| Questions | A | B | C | D | E |

| 1. How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? | Never | Monthly or less | 2-4 / month | 2-3/ week | 4+/ week |

| 2. How many units of alcohol do you drink on a typical day when you are drinking? | 1 or 2 | 3 or 4 | 5 or 6 | 7-9 | 10 or more |

| 3. How often have you had 6 or more units (for female- 8 or more if male), on a single occasion in the last year? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily (or almost daily) |

Scoring is as follows: A = 0, B = 1, C = 2, D = 3, E = 4.

A score of 3 or more in women (and 4 or more in men) indicates a possible alcohol use problem, unless all points are from question 1, in which case the service provider should review drinking patterns over the last month to get a better sense of drinking behaviour.

Other validated screening tools for pregnant or young women that providers may be interested in using include the T-ACE, CRAFFT, and TWEAK.

Additional Strategies for Having Conversations About Alcohol

Workbooks

Workbooks and print and online fact sheets can be helpful for women to learn about the issues and reflect on their use and options for change.

Knowing your Limits with Alcohol: A Practical Guide to Assessing your Drinking uses a motivational interviewing approach to facilitate thinking through readiness for change and what actions can be taken to elicit change.

Thinking About Pregnancy: A Booklet to Reflect on Alcohol Use Before You are Pregnant, a new booklet from CanFASD Research Network and the Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health, is a key resource for reaching people in the preconception period. Included in the booklet is information about standard drink sizes, why thinking about alcohol before you are pregnant is important, mocktail recipes and activities that help women reflect on what they like or dislike about drinking, what alternatives to alcohol use may be in their ‘toolbox’, and who is and will be by their side as they make change.

Discussing Multiple Substances and Issues

Brief interventions can also be used to discuss multiple issues or substances at the same time. This approach can make brief interventions more engaging and can be more effective in addressing multiple health issues. For example, adding discussions about alcohol and contraception into alcohol brief interventions can improve the outcomes for all three15,16,17.

Supporting Individuals with FASD

It is important to consider that the stigma attached to FASD, mental illness, and/or substance use creates a barrier to success for all those who seek help. Clients with FASD experience the additional stigma of having FASD and having consumed alcohol18. There are many ways we can tailor our discussions of alcohol to support people with cognitive and other learning disabilities. We must move towards FASD-informed programs that set what is in place for the individual to succeed19.

Supporting Individuals at Higher-Risk

Women’s substance use does not occur in isolation. While some women with substance use concerns may only require brief interventions to reflect on or reduce their substance use, others may require additional support. The most effective programs for women will not only support women in reducing their substance use, but also link support to child welfare, health care, housing, nutrition, and social support4.

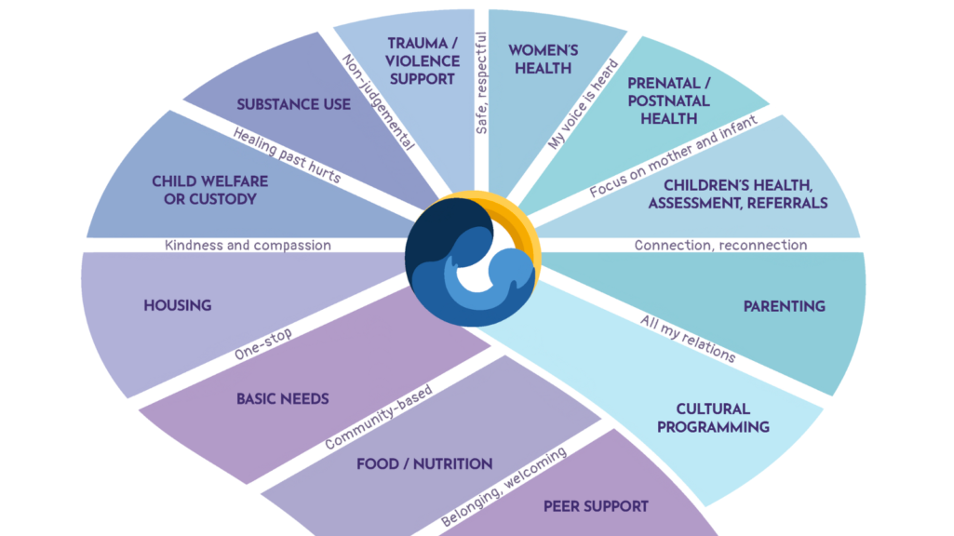

Across Canada, there are multiservice programs to support pregnant and postpartum women with substance use concerns. This integrated service delivery can support change on multiple health and social issues through providing holistic care for mothers, babies, and the mother-child relationship. Critical components of multidisciplinary integrated programs include a focus on empowerment, enhanced access to and coordination of care for clients, cross-sectoral collaboration, and individually tailored service delivery across the life course20.

The Co-Creating Evidence Project evaluated eight multidisciplinary integrated programs supporting women at high risk of having an infant prenatally exposed to alcohol or other substances. This graphic shows how multiple services for women’s various needs can help support clients in many aspects of their lives.

In this video, Manito Ikwe Kagikwe (the Mothering Project), a multidisciplinary program which supports women with substance use challenges on their journey of healing and belonging, is explained: The Mothering Project

Other successful programs include the Parent-Child Assistance Program (PCAP), which is designed for pregnant women or new mothers (within 6 months postpartum) who have used substances during pregnancy and need support for connecting to local services21. PCAP is a scientifically validated paraprofessional case management model that originated at the University of Washington and is now delivered extensively throughout Alberta (through Alberta PCAP Council) and BC (through First Nations Health Authority).

Other modalities of support include:

- Specialized live-in addiction treatment and recovery programs for women and their families. The goal of these programs is to support women with problematic substance use to help them develop healthy lifestyles. Some programs, such as the 2nd Floor Women’s Recovery Centre in Cold Lake, Alberta, offer priority to women who are pregnant or at risk of getting pregnant. Other programs include Aventa in Calgary, the Jean Tweed Centre in Toronto, and the Heartwood Centre for Women.

- Case management is an approach that involves collaborative planning, coordination, and monitoring of the services needed to meet a client’s health and human service needs. Case management has been found as an effective approach for reducing alcohol use in pregnancy. Paired with Housing First services, it has been seen in addressing the multifaceted needs of pregnant and early parenting women who are experiencing homelessness and substance use concerns.

- Mentoring and home visitation programs focused on reducing maternal alcohol and other substance use, increasing positive parenting, promoting child and maternal health, and improving family income and family housing have been found to be beneficial in supporting relational growth and meeting the complex needs of families with substance exposed pregnancies.

Indigenous Approaches to FASD Prevention and Healthy Beginnings

Indigenous approaches to FASD prevention and healthy beginnings focus on the ideas of land, lineage, and language to foster community-based and community-driven programming. These programs often adopt a wholistic approach that integrates culture and language, coordinates basic needs, and addresses complex challenges as part of community-based strategies for women’s health22.

Community-based, community-driven programs have been effective in expanding and decolonizing their thinking around what FASD prevention can look like, and how language, ceremony, protocols, traditional knowledge, and Elders can be incorporated into wellness programming. Many programs have identified common principles for enacting efforts on FASD prevention and healthy beginnings in their communities:

For more information on Indigenous approach to FASD prevention and healthy beginnings, click here: Indigenous Approaches to FASD Prevention

Final Thoughts

Preventing alcohol use during pregnancy can positively impact parents, families, children, and communities. However, it is important that all prevention is conducted in ways that consider impacts of stigma and are trauma-informed and strengths based.

Additional Resources

- Succinct strategies to use when engaging in brief interventions and examples of responses to challenging statements

- Women’s experiences of stigma and multi-level ideas for action

- Video on how to ask questions about substance use to women of childbearing years

- How a range of providers can engage in brief interventions

- SOGC Guidance on Screening and Counselling for Alcohol Consumption During Pregnancy

- One-pagers on the effects of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and opioids when pregnant, breastfeeding, and parenting

Download Handout

For a summary of information, download the Mental Health Resource and Practice Guide Section 8 Summary.

References

1Nathoo, T., Poole, N., Wolfson, L., Schmidt, R., Hemsing, N., & Gelb, K. (2018). Doorways to conversation: Brief intervention on substance use with girls and women. Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health: Vancouver, BC.

2Popova, S., Lange, S., Probst, C., Gmel, G., & Rehm, J. (2017). Estimation of national, regional, and global prevalence of alcohol use during pregnancy and fetal alcohol syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Global health, 5(3), e290–e299. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30021-9.

3Streissguth, A. P., Bookstein, F. L., Barr, H. M., Sampson, P. D., O’Malley, K., & Young, J. K. (2004). Risk factors for adverse life outcomes in fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 25(4), 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004703-200408000-00002

4Hubberstey, C. & Rutman, D. (2020). HerWay Home Program for Pregnant and Parenting Women Using Substances: A Brief Social Return on Investment Analysis. The Canadian Journal of Addiction, 11(3), 6-14. doi: 10.1097/CXA.0000000000000086

5Lyall, V.*, Wolfson, L.*, Reid, N., Poole, N., Moritz, K. M., Egert, S., Browne, A. J., & Askew, D. A. (2021). “The Problem Is that We Hear a Bit of Everything…”: A Qualitative Systematic Review of Factors Associated with Alcohol Use, Reduction, and Abstinence in Pregnancy. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(7), 3445. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073445

6Statistics Canada. (2020). Canadian Perspectives Survey Series 1: Impacts of COVID-19. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada.

7Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. (n.d.). COVID-19 National Survey Dashboard. Accessed from:https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-health-and-covid-19/covid-19-national-survey

8Poole, N., Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Prevention: Canadian Perspectives. 2008, PHAC: Ottawa, ON.

9Health Canada, Best Practices: Early Intervention, Outreach and Community Linkages for Women with Substance Use Problems. 2006, Health Canada: Ottawa, ON.

10Latuskie, K.A., Andrews, N. C. Z., Motz, M., Leibson, T., Austin, Z., Ito, S., & Pepler, D. J. (2019). Reasons for Substance Use Continuation and Discontinuation During Pregnancy: A Qualitative Study. Women & Birth, 32(1), e57 – e64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2018.04.001

11Muggli, E.; O’Leary, C.; Donath, S.; Orsini, F.; Forster, D.; Anderson, P.J.; Lewis, S.; Nagle, C.; Craig, J.M.; Elliott, E.; et al. “Did you ever drink more?” A detailed description of pregnant women’s drinking patterns. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 683.

12Wright, T.E., Terplan, M., Ondersma, S. J., Boyce, C., Yonkers, K., Chang, G., Creaga, A. A. (2016). The role of screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment in the perinatal period. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 215(5), 539-547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.038

13McBride, N. and S. Johnson, Fathers’ Role in Alcohol-Exposed Pregnancies: Systematic Review of Human Studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2016. 51(2): p. 240-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.02.009

14Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., McDonell, M. B., Fihn, S. D. & Bradley (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch Intern Med, 158(16), 1789 – 1795. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789

15Hanson, J.D. and S. Pourier. (2015). The Oglala Sioux Tribe CHOICES Program: Modifying an Existing Alcohol-Exposed Pregnancy Intervention for Use in an American Indian Community. International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fijerph13010001

16Ingersoll, K.S., et al., (2011). Preconception markers of dual risk for alcohol and smoking exposed pregnancy: Tools for primary prevention. Journal of Women’s Health, 20(11), 1627-1633. https://doi.org/10.1089%2Fjwh.2010.2633

17Sobell, L.C., Sobell, M. B., Johnson, K., Heinecke, N., Agrawal, S., & Bolton, B. (2017). Preventing Alcohol-Exposed Pregnancies: A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Self-Administered Version of Project CHOICES with College Students and Nonstudents. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 41(6), 1182 – 1190. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1111/acer.13385

18Morrison, K., Harding, K., & Wolfson, L. (2019). Individuals with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and Experiences of Stigma. Vancouver, BC: CanFASD Research Network.

19Pei, J., Kapasi, A., Kennedy, K.E., & Joly, V. (2019). Towards Healthy Outcomes for Individuals with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Canada FASD Research Network in collaboration with the University of Alberta.

20Hubberstey, C., Rutman, D., Van Bibber, M., & Poole, N. (2022). Wraparound programmes for pregnant and parenting women with substance use concerns in Canada: Partnerships are essential. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30, e2264– e2276. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13664

21Grant, T. (2010). Preventing FASD: The Parent–Child Assistance Program (PCAP) Intervention with High‐Risk Mothers. In E. P. Riley, S. Clarren, J. Weinberg & E. Jonsson (Eds). Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: Management and Policy Perspectives of FASD. Wiley-Blackwell.

22Wolfson, L., Poole, N., Morton Ninomiya, M., Rutman, D., Letendre, S., Winterhoff, T., Finney, C., Carlson, E., Prouty, M., McFarlane, A., Ruttan, L., Murphy, L., Stewart, C., Lawley, L., Rowan, T. (2019) Collaborative Action on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Prevention: Principles for Enacting the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Call to Action #33. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 16(9):1589. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16091589